A couple of months back, Warren Buffett published a letter to his shareholders (as he always does), and some of the key lessons are highlighted very nicely by Vishal Khandelwal (Safal Niveshak) in his post.

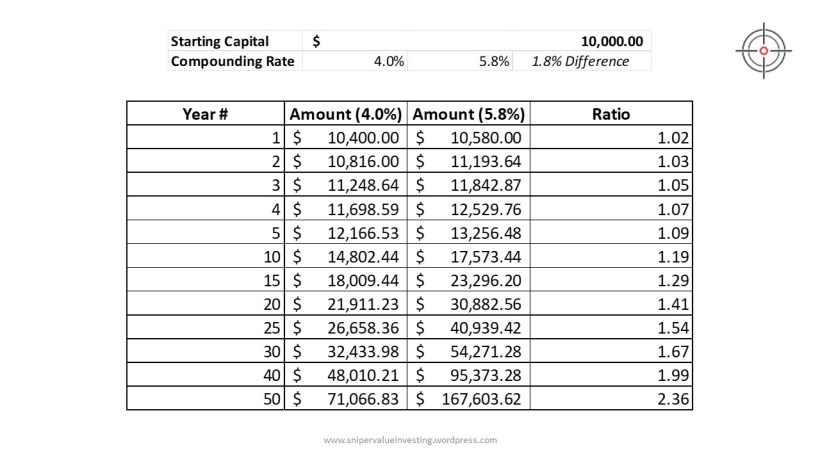

- The power of compounding. If I have a CAGR that is 1.8% higher than someone else, in 50 years’ time, my total return on my invested capital would be about 2.36x of his. You can look at this small calculation I did.

- Following up from #1, I just need 2 things: the conviction to hold when the stock is down, and time. Time to go prepare for a healthy and happy life, while looking for awesome companies to buy and hold.

- Book value is a cheat-sheet substitute for the intrinsic value of any company. Over the long term, the market will track the intrinsic value. Book value may diverge from the market value for in the short term but will converge over the long term. What this means is that we need to have the conviction to hold (or even buy more) when the markets enter a downturn.

- Focus on operating earnings, paying little attention to gains or losses of any variety. Operating earnings (EBIT) tells us the true profitability of the business. Sometimes, the net profit can be distorted by external factors out of the company’s control. As such, EBIT are more suitable when we look at companies. This is also the reason why I prefer FCF over NPAT. I would like to define a term that I will be using quite often in this post, the cash profitability margin (also called Free Cash Flow, or FCF, Margin) as:

- The math of share buyback: Each transaction makes per-share intrinsic value go up, while per-share book value goes down. That combination causes the book-value scorecard to become increasingly out of touch with economic reality. Sometimes, management tries to execute share buybacks (at all costs even) to artificially create demand for the stock price. However, this works against the long-term benefit for the shareholders.

- Buy ably-managed companies (stocks), in whole or part, that possess favorable and durable economic characteristics. We also need to make these purchases at sensible prices. Essentially, look at companies that can offer excellent value, far exceeding that available in takeover transactions.

- Let us see investing using a wide-angle lens, taking a long horizon with the objective of striving for long, sustained upwards capital appreciation rather than the short-term volatility which traders tend to focus on. Many investors fail because they fail to control their own emotions.

- A lot of times, the brand of earnings is a far cry from that frequently touted by Wall Street bankers and corporate CEOs. Too often, their presentations feature “adjusted EBITDA,” a measure that redefines “earnings” to exclude a variety of all-too-real costs. It is much better to understand the Free Cash Flow or Owners’ Earnings (as per the Shareholder’s Letter of 1986) to make a clearer judgment on the company.

- Managements sometimes assert that their company’s stock-based compensation shouldn’t be counted as an expense. And restructuring expenses? Well, maybe last year’s exact rearrangement won’t recur. However, the cost is always borne by the shareholders, not a very good sign for us unless they are really performing very well…

- Back to point #8, capital expenditures (CAPEX) can be split into two types: growth and maintenance CAPEX. Growth CAPEX is the CAPEX that is incurred for the company to scale and expand, while maintenance CAPEX is the CAPEX incurred to maintain the company’s operations in good shape. A good indication of maintenance CAPEX is the depreciation and amortization (which is why EBITDA isn’t a very good indicator contrary to what most institutional investors believe). It is important for us to differentiate between maintenance CAPEX and growth CAPEX to discuss the quality of the company. As such, I would like to introduce another term: Growth Cash Flow (GCF):

- Some people keep saying it is best for the company to declare dividends to be aligned with the shareholders. Far more important than the dividends, though, are the huge earnings that are annually retained by these companies. For companies that can earn high returns on incremental retained earnings, shareholders are better off not receiving the dividends and letting the company tap into its stronger growth potential and hence capital appreciation. These companies enjoy excellent economics, and most use a portion of their retained earnings to repurchase their shares. When earnings increase and shares outstanding decrease, owners – over time – usually do well.

- There should always be a margin of safety when we invest (which is why I always say never use margin accounts to trade, and never invest what you need to survive). By doing proper portfolio management (which I will have a podcast about), we need to set aside some cash (12 months of expenses minimum) and consider that stash to be untouchable to guard against external calamities. Avoid any activities that could threaten our maintaining that buffer. Never risk getting caught short of cash.

- In the current market, prices are sky-high for businesses possessing decent long-term prospects. In this case, it is better for us to wait than to jump into the hype that the market has created, also known as FOMO. Predictions of that sort have never been a part of our activities (and I hope it isn’t in yours too). Our thinking, rather, is focused on calculating whether a portion of an attractive business is worth more than its market price. Let us not try to predict the future but create it by making sound investment and business decisions.

- Truly good businesses are exceptionally hard to find. Selling any you are lucky enough to own makes no sense at all. Remember, never sell a high-quality business (or at maximum, sell as little as possible to recoup your capital and let the rest roll). Let the business work for you by compounding your investment returns.

- Blindly buying an overpriced stock is value destructive, a fact lost on many promotional or ever-optimistic CEOs. This is a very important lesson for CEOs and management teams (always be honest in your communication to your shareholders). Trust is the most important asset any management team can have. When a company says that it contemplates repurchases, it’s vital that all shareholder-partners be given the information they need to make an intelligent estimate of value.

- Many a times, you would see analyst estimates for quarterly earnings per share results. Never be focused on that. Quarter on quarter is simply too short-sighted for value investors like us. Let us focus on the forest rather than the individual trees. Playing with the numbers “just this once” may well be the CEO’s intent; it’s seldom the result at the end of the day. And if it’s okay for the boss to cheat a little, it’s easy for subordinates to rationalize similar behaviour. This can be seen in many cases, including Enron and Hyflux. Remember, what started off as a marginal gap between the actual operating profit and the one reflected in the books will continue to snowball and reach a point of unimaginable proportions, resulting in a whole mess. This has been compared to (by Ramalinga Raju) riding a hungry tiger without knowing how to get off without being eaten.

- The property/casualty insurance business creates a large sum in cash float, due to its collect-now, pay-later model. This float will eventually go to others. Meanwhile, insurers get to invest this float for their own benefit. Though individual policies and claims come and go, the amount of float an insurer holds usually remains stable in relation to premium volume. Consequently, as such businesses grow, so does the float of the company. This is one of the key success factors of Berkshire Hathaway. This is one of the key metrics in analyzing any insurance company. The competitive dynamics almost guarantee that the insurance industry, despite the float income all its companies enjoy, will continue its dismal record of earning subnormal returns on tangible net worth as compared to other American businesses.

- In most cases, the funding of a business comes from two sources – debt and equity. At rare and unpredictable intervals, however, credit vanishes, and debt becomes financially fatal. A Russian roulette equation – usually win, occasionally die – may make financial sense for someone who gets a piece of a company’s upside but does not share in its downside (Remember: Risk = Probability of the harm occurring x Severity of the harm). But that strategy would be madness for Berkshire. Rational people don’t risk what they have and need for what they don’t have and don’t need. Debt should only be used strategically and sparingly.

- By retaining all earnings for a very long time, we allow compound interest to work its magic. This brings us back to point #1 on the power of compounding. Beyond using debt and equity,

- Berkshire has benefitted in a major way from two less-common sources of corporate funding. The larger is the float I have described. So far, those funds, though they are recorded as a huge net liability on our balance sheet, have been of more utility to us than an equivalent amount of equity. That’s because they have usually been accompanied by underwriting earnings. In effect, we have been paid in most years for holding and using other people’s money. The final funding source – which again Berkshire possesses to an unusual degree – is deferred income taxes. These are liabilities that we will eventually pay but that are meanwhile interest-free. This gives Berkshire the ability to make money while waiting for these two sources of funds to reach a point where they must pay them out.

- Do not view your portfolio as a collection of ticker symbols – a financial dalliance to be terminated because of downgrades by “the Street,” expected Federal Reserve actions, possible political developments, forecasts by economists or whatever else might be the subject du jour. View them, instead, as an assembly of companies that you partly own. You may also want to ensure your portfolio companies, on a weighted average basis, are earning about 20% on the net tangible equity capital required to run their businesses and earn their profits without employing excessive levels of debt. Remember, shares are not mere pieces of paper. They represent a partial ownership of a business. When contemplating any investment, think like an entrepreneur or a business owner. Taking a look at Berkshire Hathaway’s holdings:

- On occasion, a ridiculously-high purchase price for a given stock will cause a splendid business to become a poor investment – if not permanently, at least for a painfully long period. Over time, however, investment performance converges with business performance. And, as I will next spell out, the record of American business has been extraordinary. A great business may not necessarily be a great investment when you overpay (buy at overvalued prices). However, in the long-term, business performance holds a much greater relevance than the original price paid. This would take many investors a long time to understand.

- Make time your friend. Start investing in the right way early to compound more. Also, just like investments, fees paid to investment managers and consultants also compound. A $1 million investment by a tax-free institution of that time – say, a pension fund or college endowment – would have grown to about $5.3 billion after 77 years. However, if the institution had paid only 1% of assets annually to various “helpers,” such as investment managers and consultants, its gain would have been cut in half, to $2.65 billion.

- In the short-term, you might panic because of stock market crisis or some government action. To “protect” yourself, you might have ditched stocks and opted instead to buy gold (let’s say 3.25 ounces for $115). After 77 years (based on past records), this would have been worth about $4,200, much less than what you would have if it was in businesses. In the long-term, stocks/businesses, if invested with the right framework, will always outperform gold.

It is time for us to reflect on our investing journey so far to make some corrections (if necessary) to our mindset…